Ensuring the welfare of Grauer’s gorillas at GRACE, the Gorilla Rehabilitation and Conservation Education Center

For this quarter’s Animal Welfare feature, ASP interviews Dr. Sonya Kahlenberg, the Executive Director of the Gorilla Rehabilitation and Conservation Education Center (GRACE) in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Dr. Kahlenberg shares the story of GRACE and considers the unique challenges involved in caring for orphaned Grauer’s gorillas in the midst of a conservation crisis. This video tells more about how GRACE is working with Congolese communities to ensure a future for Grauer’s gorillas in the wild.

ASP: What are Grauer’s gorillas, and how do they differ from mountain gorillas?

Dr. Kahlenberg: Grauer’s gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri) are a subspecies of eastern gorillas, so they are closely related to the better-known mountain gorilla (G. b. beringei). Grauer’s gorillas tend to be larger than mountain gorillas, live at lower altitudes, and incorporate more fruit into their diet. They also are only found in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), whereas mountain gorillas are in eastern DRC as well as Rwanda and Uganda. Both subspecies are Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List, but their population trends differ. The mountain gorilla population is increasing thanks to intensive conservation efforts; however, Grauer’s gorillas experienced an alarming 77% population decline over the past twenty years. The primary driver of this decline is widespread poaching for bushmeat, a practice that has been exacerbated by rampant mining for “conflict minerals” during decades of war and insecurity in eastern DRC.

ASP: What are Grauer’s gorillas, and how do they differ from mountain gorillas?

Dr. Kahlenberg: Grauer’s gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri) are a subspecies of eastern gorillas, so they are closely related to the better-known mountain gorilla (G. b. beringei). Grauer’s gorillas tend to be larger than mountain gorillas, live at lower altitudes, and incorporate more fruit into their diet. They also are only found in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), whereas mountain gorillas are in eastern DRC as well as Rwanda and Uganda. Both subspecies are Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List, but their population trends differ. The mountain gorilla population is increasing thanks to intensive conservation efforts; however, Grauer’s gorillas experienced an alarming 77% population decline over the past twenty years. The primary driver of this decline is widespread poaching for bushmeat, a practice that has been exacerbated by rampant mining for “conflict minerals” during decades of war and insecurity in eastern DRC.

ASP: Can you tell us a little bit about how and why GRACE was founded, and how you were able to get buy-in from the local community?

Dr. Kahlenberg: Infant gorillas are often captured alive during poaching events and people then try to opportunistically (and illegally) sell them for profit. By 2008, several orphaned gorillas had been confiscated by the Congolese wildlife authority and a long-term solution was needed for these individuals. The Gorilla Rehabilitation and Conservation Education (GRACE) Center was founded in 2009 to care for Grauer’s gorillas and prepare them for potential reintroduction back into the wild. Conservation education and community outreach to help curb threats to gorillas are also central to our mission. The remote Kasugho area, where GRACE is located, has a long pro-conservation history because their community leaders are committed to protecting their ancestral forests and the gorillas therein. When the idea of GRACE was developing, these leaders recruited the project to their area and even donated the land on which GRACE was eventually built. We have worked with the communities from the beginning to make this a partnership. There are real benefits for them. GRACE is the largest employer in the area and a partner in finding sustainable solutions to problems that impact local people and wildlife (e.g., poor human hygiene, food insecurity). We also invest heavily in capacity building so people gain skills needed to make this project their own. Our team in DRC is now 100% Congolese, an achievement that makes us proud and is also essential for the long-term success and sustainability of the project.

SP: The people of the Democratic Republic of Congo have endured decades of civil war. Do you find it difficult to promote animal welfare working in a country where people have suffered so much?

Dr. Kahlenberg: Unfortunately, insecurity is still a fact of life for people living in eastern DRC. Armed groups continue to operate throughout the region, fueling violence and the displacement of civilians from their homes. Understandably, it is difficult for anyone faced with these circumstances to prioritize anything other than the safety and basic needs of their family. We therefore have our work cut out for us when it comes to promoting animal welfare and conservation. We see this as an opportunity, however, and are incorporating more humane education into our work as a result. Humane education teaches empathy and encourages compassion for other people as well as animals. I think this approach has the potential to be powerful in a place like DRC where tribalism and xenophobia run deep. Our caregivers are also wonderful ambassadors for animal welfare in their communities, and we have them share their work with others as often as possible. This leads to good discussions about our relationships with and treatment of animals and the special connection that exists between humans and gorillas in particular. Empowering current and future leaders also has to be part of welfare and conservation education. We focus on youth and community leaders—particularly women’s groups—in our conservation clubs and other outreach programs. People are eager to get involved, so we see GRACE’s role as facilitating their ideas then standing back to watch them take off.

ASP: Are there any Grauer’s gorillas in captivity outside the Democratic Republic of Congo? Does GRACE help educate other facilities about how to care for these animals?

Dr. Kahlenberg: A few Grauer’s gorillas have lived in zoos over the years, but as far as we know, only one is still alive (Antwerp Zoo in Belgium). We have not had contact with this zoo, but we do partner with other great ape sanctuaries and in-country veterinarians to help train staff and share best practices. We have recently led caregiver exchanges with two other chimpanzee and gorilla sanctuaries to facilitate cross-training.

ASP: Do you find husbandry practices and standards of care developed for western lowland gorillas are effective with this species, or do they have to be altered in certain ways to fit the needs of Grauer’s?

Dr. Kahlenberg: Early on, we enlisted the help of veterinarians and animal managers from AZA [Association of Zoos and Aquariums] zoos because they are the world’s experts in gorilla care. Gorillas are challenging because they require specialized diets and infants in particular can be very fragile when stressed. Managing multiple males in a social group is obviously difficult too, since they tend not to tolerate each other once they enter adolescence. We’ve been able to successfully apply protocols developed by zoos for western lowlands, such as using positive reinforcement techniques to manage intra-group aggression and to facilitate health assessments. Our zoo advisors have pointed out that Grauer’s gorillas seem more behaviorally flexible and to learn more quickly than western lowlands. We have not studied this formally, though, so it’s unclear whether this is a real difference or influenced by the individuals we have at GRACE. We’ve also had to tailor some practices specifically for Grauer’s gorillas and for our rehabilitative mission. For example, to ensure the gorillas get a >90% wild diet, we gather 300 lbs. of vegetation each day to supplement the food the gorillas forage for in the forest. The plant species we target are foods eaten by Grauer’s gorillas in the wild.

ASP: Most of the gorillas at GRACE arrive as infants that have experienced significant trauma. What approaches do you use to help them recover from these early life experiences?

Dr. Kahlenberg: It is necessary to use human caregivers when gorillas first arrive because they go through a 30-day quarantine, but we have found that the most effective way to help gorillas heal from psychological trauma is to get them in with other gorillas as soon possible. We have fourteen gorilla orphans (eleven females, three males), and they live together in a single group. Some of the gorillas were confiscated a while back, so they are now adults. We introduce new gorillas to the group, and one of the adult females assumes the role of surrogate mother. Introductions need to be carefully planned, which is one of the reasons why zoo advisors have been invaluable to us. So far, every one of our eight introductions has been successful. Surrogate females carry, play, share food and sleep with infants as well as protect them within the group—just like a biological mother would. This bond seems to develop quickly and it lasts too. For example, we have a seven-year-old male who continues to have a close relationship with his surrogate mother even though she’s now caring for a two-year-old. The three stick together within the group as a little family unit. We have seen some dramatic turnarounds as well. One four-year-old female arrived after spending three years with only human companions. She had plucked out much of her hair and used aggression to lash out at caregivers. Once in the group, her hair plucking stopped and she became much more calm. The resiliency of these gorillas never ceases to amaze us.

ASP: How does GRACE promote positive welfare for gorillas in your care and how do you evaluate welfare?

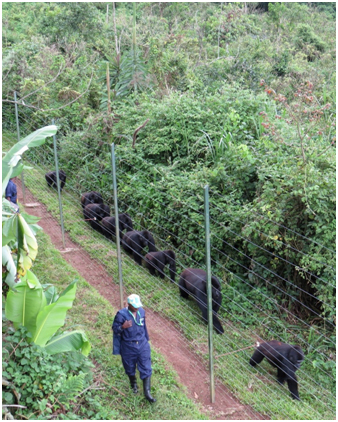

Dr. Kahlenberg: Our approach to promoting positive welfare is to give the gorillas the most natural life possible. In addition to living in a surrogate family group, the gorillas also live in a 24-acre forest habitat where they can engage in a full range of natural behaviors such as foraging, building nests, and coordinating group travel. We are now in the process of adding fifteen more acres to this habitat to give them even more forest to enjoy. In the forest, the gorillas forage for the majority of their food themselves. We also give them as much choice as possible. For example, they can choose to sleep indoors or in the forest, and they have freedom to access every part of the forest. Since we only monitor them from the perimeter fence, the gorillas can spend their whole day out of sight, if they so choose. Additionally, we use positive reinforcement methods to minimize the stress of veterinary interventions. To track welfare indicators as well as rehabilitation progress, we observe the gorillas each day and record behavior of the group as well as individuals. We also conduct detailed daily visual assessments to look for any health issues. We are hoping to soon add a hormonal component to our monitoring program as well. In general, the behavior of the GRACE gorillas seems to be similar to that of their wild counterparts. Hair plucking and regurgitation and reingestion, behaviors that are seen in zoo gorillas, are very rare at GRACE.

ASP: How will your standards for evaluating welfare differ in the context of reintroductions, when the gorillas are no longer living in a captive setting?

Dr. Kahlenberg: This is something we are actively discussing now. Part of the difficulty is that reintroduced gorillas will need to be monitored remotely since researchers could be at risk if they follow them on foot, given that they were captive animals. Therefore, the data we collect to evaluate welfare of individuals will likely be determined by the type of remote monitoring technology we use. We are still investigating the options that are available and appropriate for gorillas.

ASP: Do you find that there are trade-offs or conflicts between conservation goals like reintroduction and animal welfare goals?

Dr. Kahlenberg: Although we haven’t yet arrived at the reintroduction phase of our project, we are actively planning for this scenario. Certainly there will be trade-offs that will need to be carefully considered. For example, it is unlikely that we will be able to reintroduce the entire group, because some gorillas have suffered significant injuries that would give them little chance of survival in the wild. So at some point we will need to consider breaking up the group, which will obviously be a difficult change for the gorillas. Of course, living in the wild will also be more challenging for the gorillas than their current life at GRACE, so we have to make sure release candidates are well prepared and closely monitored after release to ensure they are adjusting appropriately.

ASP: What is the planned timeframe for a reintroduction?

Dr. Kahlenberg: This is hard to answer as the political situation in DRC is pretty tense right now, and there’s been a resurgence of security concerns. We have to get the timing right, so we are willing to be patient and wait for the best opportunity. That said, we are currently working with scientists with expertise in gorilla ecology and veterinary medicine as well as great ape reintroduction to help us prepare. Ultimately, we would like to see the GRACE gorillas get a second chance at being wild, but in the meantime, we will do everything we can to give them the next best thing.

To learn more, visit http://gracegorillas.org/