Physical Therapy for Chimpanzees

For this quarter’s Hot Topic, we are featuring the work of Dr. Sarah Neal Webb, Jennifer Bridges, and Erica Thiele, who created, implemented, and evaluated a physical therapy (PT) program for chimpanzees at the Center for Chimpanzee Care in Bastrop, Texas, which is part of The MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Michale E. Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research (KCCMR). Dr. Neal Webb is a Research Investigator at the KCCMR currently working with baboons, and Ms. Bridges and Ms. Thiele are trainers working with the chimpanzees and baboons at KCCMR. For this featured project, personalized therapy programs were created for nine chimpanzees with mobility issues using positive reinforcement training (PRT) and then empirically evaluated using a variety of measures. Throughout the course of the 6-month program, chimpanzees’ ratings of well-being and mobility showed significant improvement compared to control chimpanzees without mobility issues as well as compared to baseline. These findings were published in the American Journal of Primatology in 2020. Here, Dr. Neal Webb, Ms. Bridges, and Ms. Thiele participate in a question and answer session regarding some details and applications of the PT program.

How did you decide which animals to include in the PT program?

We have a colony that, like many chimpanzee colonies, is aging, and an increasing number of chimpanzees are classified as geriatric (35 years and older). With age comes a variety of mobility impairments, including impairments caused by arthritis, stroke, and previous injury. At the Center for Chimpanzee Care in Bastrop, Texas, the people involved in the care of the chimpanzees are trained to monitor animals for signs of mobility issues, and veterinarians and veterinary technicians monitor animals for arthritis and other health conditions during daily health checks, as well as during annual physical exams. Therefore, we maintain a list of animals with these types of health and mobility issues so that we can monitor them daily. Using this list, we identified chimpanzees whose mobility could benefit from increased strength or flexibility (the goal of the physical therapy program) and consulted with the veterinarians. Based on their feedback, our final list of chimpanzee participants consisted of chimpanzees with mobility issues due to arthritis, previous stroke, and previous injury.

How did you determine which exercises to use?

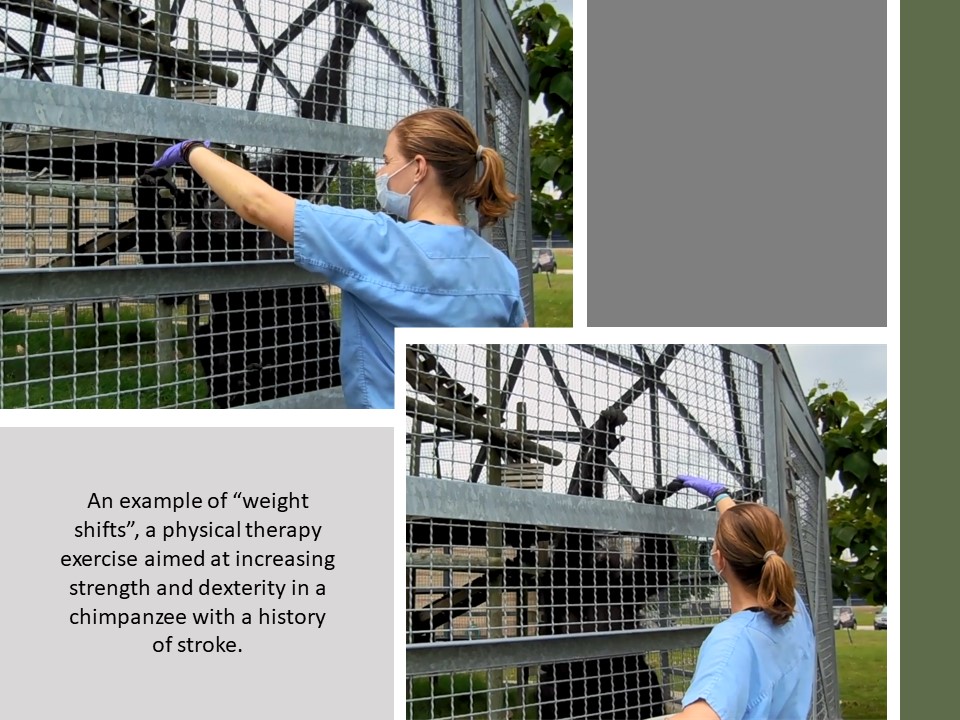

One important goal of our PT program was to create individualized programs for each chimpanzee, so we created personalized exercises based on each individual’s mobility issue(s), physical limitations, and their training preferences. For example, chimpanzee ROS presented with arthritis in her hips and knees. To increase flexibility and strength in her legs, we chose to attempt squats and bouts of standing. We started with these exercises knowing that we would need to evaluate both the effectiveness of the exercise(s) and the chimpanzees’ comfort level in performing the particular exercise(s), so we met with the therapy team frequently to make sure we were not pushing the animal beyond his or her comfort level. Obviously, an animal that presents with arthritis (like ROS) is going to have different exercises than an individual with mobility issues due to stroke. For chimpanzees with a history of stroke and paresis, our goal was to increase strength (e.g., standing, climbing) and/or dexterity (e.g., finger and toe extensions). For each animal, we discussed the potential need to change the exercise type or duration depending on performance and comfort level as part of their personalized routine. We also kept training preferences in mind for each animal. For example, ROS preferred to use grapes for her standing exercise while SAB preferred juice.

What methods can you use to evaluate the effectiveness of physical therapy and ensure that it has its intended effects?

It is best to have a point of comparison, perhaps a control group or a baseline period so that you can compare pre- and post-therapy mobility. In the study, we did both. We had a control group of chimpanzees without mobility issues that participated in PRT sessions instead of PT for the same frequency and duration as the PT chimpanzees to attempt to separate the effects of increased human attention from the effects of the PT. We also started collecting our data (using the measures described next) before the onset of the PT program and treated this as the “baseline” phase that we could use to compare post-PT mobility.

Regarding measures that can be used: ultimately, there are many ways to empirically evaluate the effects of a physical therapy program. Since this study was more of an initial evaluation of the implementation of this new program, we chose outcome measures that were cost-effective and easy to obtain. We used caregiver ratings of wellness, which were efficient and effective. The rating sheets were conveniently posted outside of each animal’s area and took only a small amount of time to complete. The caregivers were not blind to the fact that the animals were participating in PT, but we ensured that they were blind to the details of the PT (e.g., what phase the animal was in, days of therapy, etc.). We also used measures to which we had access, like comments recorded by the veterinarians during annual physical exams. Lastly, we used mobility scores to rate movement ability and agility, which is a tool that has been previously used in the colony to monitor cases of mobility concern. Other observational methods would also be very valuable (e.g., focal animal sampling of select behaviors), but they are more time-consuming. Overall, we would recommend using several methods to capture different aspects of the ways that PT may be affecting the animals.

Importantly, as we mentioned in the previous answer, we also met frequently to ensure that the PT program was not having unintended consequences. For example, we monitored closely for signs of increased mobility issues, pain, stiffness, lack of movement, depressed behavior, etc. We also monitored for signs of changes in social dynamics to ensure the extra attention from the PT did not cause aggression within the group. We wanted to ensure that the PT program was having a positive effect on the welfare and that we were not causing harm unintentionally. By meeting frequently and involving care staff, veterinarians, and veterinary technicians, we ensured that no such consequences occurred.

What would be the next steps for this program? What is the long-term goal of the program?

For ailments such as arthritis and stroke, it is important to continue PT so that the beneficial effects on mobility continue. We planned to continue the program, including increasing the number of PT sessions per week and continuing to empirically assess the effects of the program. Unfortunately, the COVID pandemic interrupted these plans. Currently, three chimpanzees are participating in PT as part of their wellness routine, but we are not currently collecting data for evaluation purposes. The long-term goal would be to transfer the PT training to interested care staff who could implement PT as part of the chimpanzees’ weekly routine. We’d also like to use PT for injury recovery, and perhaps also use the PT principles (e.g., personalized programs based on individual needs, empirical evaluation, etc.) to implement an exercise program for overweight chimpanzees.

Your study examined PT in chimpanzees. Can PT be implemented in other species?

Absolutely! PT is simply utilizing PRT to create a routine that encourages movement, stretching, or strength building. Therefore, any animals that respond to PRT and could benefit from increased mobility would likely be good candidates for a PT program. In building the exercises using PRT, trainers will likely need to start by evaluating the training level of the animals. At our facility, the chimpanzees were very familiar with PRT and had already been trained on several body exam and movement behaviors, so we simply needed to build on existing behaviors. If working with naïve animals, they first would need to be conditioned to a clicker (or an alternative secondary reinforcer) before behaviors can begin to be shaped. Body exam behaviors and target training are often good behaviors to start with and, as mentioned above, are foundation behaviors on which to build PT exercises. Once an animal is conditioned to a secondary reinforcer and introduced to the training process, particularly through learning basic body exam behaviors, then eliciting particular movements is relatively easy for the animal to learn. Animals that experience strokes and lose partial function of one or more extremities often require more work initially to help them regain the connection that is required for them to move the limb into a specific position for PT. In our experience, repetition and consistency help these animals become accustomed to a PT program, thereby making it easier to adjust or add various movements when necessary.

Are there any other therapies that you use, outside of medication, that complement the PT program?

Along with PT, we also use acupuncture and laser therapy, both of which are used to target inflammation in arthritic areas, and to treat animals with mobility issues (Magden et al., 2013). Acupuncture entails the insertion of thin, sterile needles into highly innervated and vascular acupuncture points. Laser therapy involves using a handheld device with a clear rod that allows the therapeutic laser to precisely target a particular point. Because we were interested in assessing the effects of the PT program on health welfare, we did not implement these therapies in the nine PT chimpanzees that participated in the PT study. However, we do use these therapies for arthritis and injuries, and our team has demonstrated that participation in acupuncture therapy has resulted in improved mobility scores (Magden et al., 2013).

Like the PT program, both acupuncture and laser therapy require PRT. For both therapies, we train the chimpanzees to present the desired part of the body and then hold for the amount of time that the veterinarian has deemed necessary for their treatment (typically five to ten minutes). Because acupuncture involves the use of needles, the chimpanzees must also be desensitized to the acupuncture needles and to the presence of the veterinarian since the veterinarian must apply the acupuncture treatment. As such, the positive reinforcement trainer and veterinarian work together during the final stages of the acupuncture training process. Because there are no sensations associated with the laser, the training process for laser therapy is shorter than for acupuncture.

Reference

Magden, E. R., Haller, R. L., Thiele, E. J., Buchl, S. J., Lambeth, S. P., & Schapiro, S. J. (2013). Acupuncture as an adjunct therapy for osteoarthritis in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science, 52(4), 475-480.